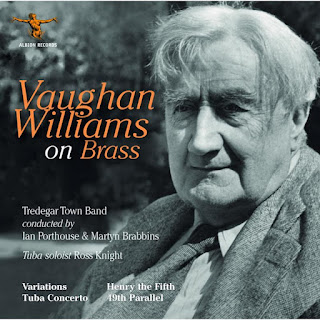

This survey of Ralph Vaughan

Williams’s brass band music opens with the short Flourish for Band,

originally devised for wind band, and first heard in 1939 at a pageant Festival

of Music and People at the Royal Albert Hall. This event had been organised

by Alan Bush. It is typically bold, brash and strident in tone, with a quieter

middle section. It was later arranged by Roy Douglas in 1972 for brass band.

This recording uses a new edition of the score prepared by Phillip Littlemore.

No introduction is needed to the English Folk Songs Suite written in 1923: it was formerly scored for military band and was later adapted for full orchestra the following year by fellow composer Gordon Jacob. Frank Wright made a version for brass band in 1956. The present score was prepared by Littlemore. The three movements are March: Seventeen Come Sunday, Intermezzo: My Bonny Boy and March: Folk Songs from Somerset. It is the first that has become popular with listeners to CLASSIC fM.

The Sea Songs were initially scored for military and brass bands in 1923. It was later transcribed in 1942 for full orchestra by RVW. The first performance was “almost certainly” at the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley in 1924. The three tunes majored on include Princess Royal, Admiral Benbow and Portsmouth. Once again Phillip Littlemore has made a brilliant new edition for brass band.

The first of RVW’s “original” brass band pieces on this CD is Henry the Fifth. There is some doubt as to when it was composed. The liner notes suggest that it could have been written for the 1934 Abinger Pageant. The overture was formally premiered in Miami, Florida in 1979 and here in the UK the following year at Thetford, Norfolk. The performing edition had been prepared by Roy Douglas. The work uses four traditional melodies: two French and two English. The opening is based on the Agincourt Song, celebrating Henry’s victory over the French in 1415. It is a powerful, sometimes scary arrangement of this tune. Tranquillity appears in the form of the Provençal air Magali followed by the marching song, Réveillez-vous Piccars. This latter is real battle music. The Overture ends with a reprise of the Agincourt Song followed by an arrangement of William Byrd’s Earl of Oxford’s March embellished with elaborate fanfares.

Three admirable arrangements

follow. The Truth from Above makes use of the eponymous folk song sung

to the composer by Mr W. Jenkins of King’s Pyon in Herefordshire (1909). RVW also

used it in the opening of his Fantasia on Christmas Carols (1912) and later

in the Oxford Book of Carols. It opens with a tuba solo and explores

various settings of the tune, before building up into a stately climax. The

last notes are played by the tuba. It has been realised by Paul Hindmarsh.

The Prelude on Rhosymedre was transcribed by Hindmarsh for brass band in 2008 to mark the 50th anniversary of RVW’s death and was premiered at the Royal Northern College of Music Festival of Brass. This beautiful meditation is most often heard in the original organ solo (1920), or occasionally in its orchestral version (1938) by Arnold Foster.

The 49th Parallel was a successful wartime film following the exploits of the crew of a German U-boat sunk in Canada’s Hudson Bay as they try to reach the then neutral United States. Vaughan Williams provided the film score. The Prelude: The New Commonwealth is often played and regularly heard on CLASSIC fM. In 2004 Chandos Records issued a Suite of this music arranged and edited by Stephen Hogger. It was of symphonic proportions lasting for nearly 40 minutes. The present offering for brass band was devised by Paul Hindmarsh and arranged by Philip Littlemore. It includes the film’s opening scenes, some pastoral images of the Canadian landscape, a scary Lutheran chorale and the “mechanical, jaunty Control Room Alert with its persistent drive and energy.” Also featured briefly is the haunting The Lake in the Mountains, subsequently issued by RVW as a piano solo. And finally, the sumptuous Prelude, brings this superbly dramatic suite to a satisfying and quite moving conclusion.

The second “original” brass band work was completed in 1955. The Prelude on Three Welsh Hymn Tunes was first publicly heard during a BBC broadcast on 12 March of that year. The liner notes describe it as an “uncomplicated arrangement, flowing seamlessly from a reverential opening to a noble, triumphant climax.” I am not quite convinced by the word “uncomplicated” here. It seems to me that there is much going on the in the instrumental contrasts and interesting variety of changes to tempo. The three hymn tunes used are Ebenezer, Calfaria and Hyfrydol. It is a well-balanced piece that is “expansive and festive,” as well as having some reflective moments.

The Tuba Concerto in F major was a commission for the Golden Jubilee of the London Symphony Orchestra for 1954. It is often regarded as the first viable concerto devised for this instrument. The work is in three movements, with a beautifully wrought Romanza being bookended by a bouncy Prelude and a vivacious Rondo alla tedesca. Both fast movements have virtuosic cadenzas. The Concerto was originally scored for soloist and a “theatre orchestra.” An early review described it as “a curiosity rather than a convincing work or art” and the “lumbering gait of the solo tuba, like that of a sea-lion negotiating a step ladder, arouses interest rather than pleasure.” History has proved that not only is this probably RVW’s best known concerto but is regarded as a perfectly stated exploration of the possibilities of the solo tuba. The performance by Ross Knight is exceptional in every way. He makes his instrument dance and sing its journey through the entire concerto. The present brass band arrangement is by Philip Littlemore

The last of the three original

brass band compositions on this CD is the Variations for Brass Band. Written

as a commission for the 1957 National Brass Championships. The original score

was edited by Frank Wright, who described it as being “a new landmark in the

history of contesting – perhaps the most significant in the whole history of

brass bands.” The new edition heard on this CD has been prepared (once again) by

Philip Littlemore and published by Boosey & Hawkes: it corrects a “vast number

of errors” and “is substantially different than Frank Wright’s contest edition

published for the 1957 contest.”

Of interest here is the origins

of the main theme. It first appeared in the early orchestral work, Triumphal

Epilogue dating from 1901. It was to reappear in the tone poem The

Solent (1903), the Sea Symphony (1903-09) and latterly in the slow

movement of the Symphony No.9 (1956-58). It clearly had some special meaning for

Vaughan Williams. There are eleven variations which include dance movements,

such as a waltz, an arabesque and a Polacca and some more cerebral offerings

such as Canon and Fugato. There are some reflective moments as well, including

the sad Adagio. The work concludes with a final Chorale.

The Tredegar Town Band under both their regular musical director, Ian Porthouse and their guest conductor Martyn Brabbins give enthusiastic performances of all this repertoire. I have noted above the remarkable contribution by Ross Knight.

The fulsome liner notes by Paul

Hindmarsh and Philip Littlemore were a pleasure to read and give a genuinely

helpful account of all the music. The sound quality of the recording is

excellent.

This new CD, made under the

auspices of The Ralph Vaughan Williams Society, is a splendid contribution to

the 2022 celebrations of the 150th anniversary of the composer’s

birth. For those of us of certain age, it does not seem that long ago when we

were celebrating his centenary in 1972!

Flourish for Band (1939)

English Folk Songs Suite (1923)

Sea Songs (1923)

Henry the Fifth (1934?)

The Truth from Above (??)

Prelude on Rhosymedre (1920)

Suite from 49th Parallel (1941)

Prelude on Three Welsh Hymn Tunes (1955)

Tuba Concerto in F minor (1954)

Variations for Brass Band (1957)

Ross Knight (tuba)

Tredegar Town Band/Ian Porthouse, Martyn Brabbins (The Truth from Above, Prelude on Rhosymedre and Variations)

rec. 4-5 December 2021 and 25 March 2022 (Tuba Concerto), Brangwyn Hall, Swansea.

ALBION RECORDS ALBCD052