Performance. It has not been possible to trace the Viola Sonata’s

first performance in the literature. It was heard on the 28 June 1946 at the

Birmingham Midland Institute School of Music in a recital by Lena Wood (viola)

and Tom Bromley (piano). Whether this was the premiere is open to conjecture.

Geoffrey Self (op. cit., p.54) alludes to the fact that Harrison’s one-time teacher, the redoubtable Sir Granville Bantock heard it in 1946. It is not understood if this was a private or public recital. The Sonata appears to have disappeared into the mists of time. It is self-evident that contemporary musicologists tended to see the Sonata as being somewhat light-weight and dated. It was written in a style that manifestly looked back to the past rather than forward to anything vaguely resembling the avant garde! There is not a tone row to be seen in any part of this work!

On Friday, 24 August 1951, Julius Harrison’s Viola Sonata was broadcast on the BBC Home Service. Watson Forbes played the viola and was accompanied by Alan Richardson. The programme also included several songs sung by the baritone, Williams Parsons. A recording of this has been uploaded to YouTube.

Publication & Review. The Sonata was published by Lengnick in 1946 to a good critical reception. The glowing words on the advert are worth quoting – “This Sonata…is characteristic of Harrison’s mature powers, is considered by many judges to be the most notable addition to the Viola repertoire that has occurred within recent years.”

Jean Stewart wrote that working on the Sonata with him [Harrison] was a lesson in itself...’ he had the most acute ear for balance, intonation, phrasing, the colour of different keys, and the give and take of chamber-music playing.’

An unsigned review of the score in the Musical Times (November 1946, p.336) notes that Harrison is not well known as a composer – but as a conductor. Yet the critic was impressed and suggested that it revealed talents that are far from common. He feels that he has a deep understanding of both instruments, and this expresses itself in the technical underpinning of the Sonata. He states that it is important to indulge in “sound melodic writing which does not mean cheap and conventional design but a design that gives the instrument the right opportunity to make use of its best registers.” He concludes by insisting that the Viola Sonata is an “honest and genial piece of work and a valuable addition to the extremely scanty repertory of viola and piano.”

A later review of the score in

the January 1947 issue of

It is difficult to know if his

prediction came true. Sixty years later this solo instrument appears to be largely

ignored in the concert halls and recital room – at least in the United Kingdom.

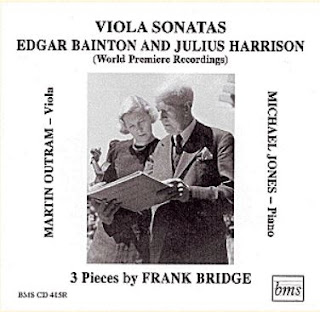

Recordings. The first (and to date the only) recording of Harrison’s Viola Sonata was made by the British Music Society in December 1992. It was an important release that combined two ‘rare and substantial’ British Viola Sonatas. The other compositions on this CD include the Edgar Bainton Sonata written in 1922 and three short numbers by Frank Bridge. The performances are everything that could be wished for and both Martin Outram (viola) and Michael Jones (piano) present these premieres in a positive and challenging manner. Rob Barnett, reviewing this recording for MusicWeb International, (4 July 2004) states that these “two resolutely strong and poetic sonatas…represent writing and playing of a very high order bursting the bounds of conventionality.” He concludes by insisting that this disc is “certainly a de rigueur purchase for open-minded violists!”

The Julius Harrison’s Sonata for Viola and Piano in C minor has great depth and quality. There are two reasons why attention needs to be given to this work. Firstly, the overall impression of the Sonata is totally satisfying. There is no point at which the listener loses interest. The equilibrium of the movements and the balance of the soloists are superb: the writing for both the violist and the pianist is grateful to both performers - with the exception noted above. And secondly, the composer is beholden to no-one in the stylistic approach of his music. True, a few influences could be discovered at many points in this work. Yet the fact remains that it is quite individual. It can be regarded as Julius Harrison’s meditation on the English Landscape, both physically and spiritually, at the end of the Second World War, the reflection of the sadness of the previous six years and finally the optimism for the coming decades. As such it is entirely successful.

Discography: Edgar Bainton (1880-1956): Viola Sonata, Julius

Harrison (1885-1963): Viola Sonata in C Minor, Frank Bridge (1879-1941):

Allegretto, 2 Pieces. Martin Outram (viola), Michael Jones (piano). British

Concluded.