As can be divined from the CD’s

title and track-listing, this is a journey through the Church’s Year, with specific

reference to Lincoln Cathedral. It is appropriate in this secular age that the

excellent liner notes include a succinct, but informative, two-page

introduction to the progress of the Christian Year. This detail will not be a revelation to most

enthusiasts of this kind of music, but hopefully, it will be rewarding to

listeners who have little connection with the tradition.

As I complete this review, we are

in preparation for the Birth of Jesus Christ on 25 December 2018. Even though

this has been ongoing since the middle of September in many shops, the true beginning

of the Christmas Season and the Christian Year was Advent Sunday on 2 December

past.

The Choir of Lincoln Cathedral begin

with a thoughtful, but ultimately urgent, account of William Byrd’s setting of

St Mark’s text (Mark 13: 35-37) enjoining the faithful to watch for the coming

of the Lord: ‘Vigilate’. This is

followed on Christmas Day by the well-known traditional French carol ‘Ding Dong

Merrily on High’ in the Wilberg and Stevens arrangement. The organ part in this

version is particularly stunning. Felix Mendelssohn’s ‘There shall a star from

Jacob come forth’ featured in the unfinished oratorio Christus. This anthem celebrates the coming of the Three Kings and

the Epiphany (manifestation) of Jesus as the Christ to the Gentiles with

reference to New Testament ‘history’ and Old Testament ‘prophecy’. It is

clearly an attractive and popular piece, but I find that it is just a bit

insipid. The work is in three sections,

opening with a recitative, followed by a trio and concluding with a chorus.

Very shortly after putting away the

Christmas decorations, the Shrove Tuesday pancakes are being made and Ash

Wednesday is upon us. This is the start of Lent which is a season of preparation.

This includes, for Christians, a personal and global recognition of the sinful

nature of humankind, individually and collectively. Samuel Sebastian Wesley’s

High Victorian anthem ‘Wash me Thoroughly’ meditates on the need for forgiveness.

Look out for the long-breathed melodies, gorgeously subtle harmonies and

delicious suspensions. It is a perfect miniature.

Edward King was an Anglo-Catholic

(High Church) bishop of Lincoln who died in 1910. He is fondly recalled by this

‘wing’ of the church and is commemorated with a ‘black letter day’ or ‘lesser festival’

on the date of his death, 8 March. Patrick Hawes, well known for his Highgrove Suite and lately his Great War Symphony, has provided a

lovely anthem. ‘My Dearest Wish’ which is based on texts from the King’s

writings. It has a ‘wide-ranging’ vocal line, gorgeous harmonies and is

accompanied by a well-judged organ part. Truly lovely: a credit to Bishop

Edward King’s life and work.

The Feast of the Annunciation is usually

held on 25 March. Clearly this is

exactly nine months before Christmas Day. Sometimes, this is in the middle of

the Easter Celebrations when it is ‘translated’ to a suitable date after Easter

Monday. Robert Parsons, who was a near-contemporary of William Byrd, is the

source of a characteristic setting of the Angel Gabriel’s words ‘Ave Maria’- ‘Hail

Mary.’ This is a deeply-considered anthem which gives rapt attention to the

text and provides a heart-easing blessing on this auspicious day in the

Church’s calendar. It is believed that poor old Parsons drowned in the River

Trent at Newark. William Byrd succeeded him as one of the Gentlemen at the

Chapel Royal.

It is now time to enter

Passiontide. This is taken as the last two weeks of Lent ending on Holy

Saturday. The choir have chosen Richard Lloyd’s idiomatic setting of the

spiritual ‘Were you there when they crucified my Lord?’

Thomas Tallis’s Salvator Mundi (O

Saviour of the World) has been selected to recall the darkness of Good Friday

when the Christ died on the Cross. It was published in the 1575 volume Cantiones Sacrae which was a joint

enterprise with William Byrd. This perfectly engineered anthem sees the opening

plainchant develop into the wonderful world of polyphony.

Few listeners to ecclesiastical

music can be unaware of Bob Chilcott’s contribution to the genre. The present

anthem for Easter is not a triumphant shout, but a profound contemplation, inspired

by a text by George Herbert, ‘The Arising’. This anthem showcases Chilcott’s

wonderful harmonies and magical melodic lines. It is a restrained work that considers

the spiritual, rather than the historical, aspect of the Resurrection on Easter

Day.

The Feast of the Ascension, where

Jesus is taken up into heaven, is celebrated with Gerald Finzi’s largely

atypical anthem ‘God is Gone Up’. This great paean of praise was composed

during 1951 for that year’s St Cecilia’s Festival at St Sepulchre-without-Newgate

Church, Holborn Viaduct. It is far removed from the quiet pastoralism that

Finzi is typically (sometimes unfairly) recalled.

From this point onward, the

Church enters the long (seemingly interminable) period of Trinity. Look at the

Prayer Book – from the First to the Twenty-Fifth Sunday[s] after Trinity! The

present CD from Lincoln have included several liturgical highlights that occur

during this ‘teaching’ period in the Church’s Calendar.

The most ‘modernistic’ work on

this CD is Judith Bingham’s setting of the ‘Corpus Christi Carol’ which honours

the institution of the Eucharist. This

piece makes a musical journey from light to shadow.

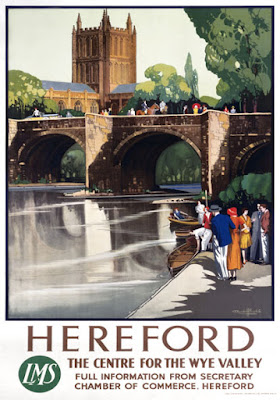

St John the Baptist’s Day (24

June) is celebrated by Sir Edward Elgar’s Benedictus in E, op.34 no.2.

This, along with its accompanying ‘Te Deum’ was composed for the 1897 Hereford

Three Choirs Festival. It was dedicated to George Robertson Sinclair. Sinclair

is reputed to have said about the work that ‘It is very, very modern, but I

think it will do.’

Charles Wood’s ‘O Thou, the

central Orb’ was selected to celebrate the Feast Day of the Blessed Virgin Mary

on the 8 September. Wood’s anthem ‘speaks of the joy of faith, the company of

the saints and the transformation of love that God brings to those who trust

him.’ His setting is largely romantic in sound with its solo bass part and

reassuring ternary form. The powerful conclusion is stunning.

The trumpet, played by Sgt Tom

Ringrose, is used to point up the effect of Mark Blatchly’s setting of Laurence

Binyon’s great poem, ‘With Proud Thanksgiving.’ The traditional bugle call of

the ‘Last Post’ is introduced during the final verse, ‘At the going down of the

sun…’ The general progression of Blatchly’s piece is a march with a singable

tune. The liner notes are correct in suggesting that this music looks back to

Elgar and the early twentieth-century.

No introduction is needed to

Johannes Brahms’s beautiful ‘Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen’ (How Lovely are

thy Dwelling Places) from A German

Requiem. It is sung here in German. This piece was picked to commemorate (17

November) St Hugh, onetime Bishop of Lincoln. The liner notes state that the

text’s ‘longing for the divine presence’ is entirely appropriate for a cleric who

worked so hard for Lincoln’s faithful and for the fabric of the Cathedral.

The penultimate track features

John Taverner’s ‘Christe Jesu, pastor bone’ chosen to celebrate the Feast of

Christ the King. This festival is usually on the Last Sunday of the Church’s

Year, that is, just before Advent. It is seen as a summing up of the events

that have gone before. Taverner’s music is restrained and forward-looking

towards the achievement ‘of Thomas Tallis and his contemporaries.’

The final track is Ralph Vaughan

Williams’s ‘Antiphon’ from his Five

Mystical Songs. These settings of George Herbert’s poetry were completed in

1911. Herbert is commemorated in the Anglican

Tradition on 27 February. So, it is a wee bit out of chronological order here

but makes a good closing number. Antiphon

is written for chorus alone. This is a great song of praise. The words ‘Let all

the world in every corner sing: my God and King,’ is the triumphant refrain.

Frank Howes has suggested that this song is a ‘moto perpetuo’ that reflects the

Sea Symphony with its

boisterousness. It is a splendid and

uplifting conclusion to both the Mystical Songs and this CD.

Great sound quality on this disc.

Excellent performances from all concerned. Splendid liner notes. This new

release from Regent perfectly presents Lincoln Cathedral Choir, the organ and

the Church’s Year. A rare treat, indeed.

Track Listing:

A Year at Lincoln:

The Choir of Lincoln Cathedral

Advent: William BYRD

(c.1538-1623) Vigilate (1589)

Christmas: Ding! dong! merrily on high 16th c

French, arr. Mack WILBERG (b.1955)

and Peter STEVENS (?/2007) (b.1987)

Epiphany: Felix MENDELSSOHN

(1809-1847) There shall a star from Jacob come forth (from Christus (1847))

Ash Wednesday: Samuel

Sebastian WESLEY (1810-76) Wash me thoroughly (c.1840)

Bishop Edward King; Patrick

HAWES (b.1958) My dearest wish (2010)

Annunciation: Robert PARSONS

(c.1535-1571/2) Ave Maria (?)

Passiontide: Were you there? Spiritual, arr. Richard LLOYD (b.1933) (1996)

Good Friday: Thomas TALLIS

(1505-85) Salvator mundi (pub.1575)

Easter: Bob CHILCOTT

(b.1955) Thy arising (2012)

Ascension: Gerald FINZI

(1901-56) God is gone up (1951)

Corpus Christi: Judith

BINGHAM (b.1952) Corpus Christi Carol (2012)

St John The Baptist: Edward

ELGAR (1857-1934) Benedictus in F, Op 34 no 2 (1897)

Blessed Virgin Mary: Charles

WOOD (1866-1926) O Thou, the central orb (1915)

Remembrance: Mark BLATCHLY

(b.1960) For the fallen (1980)

St Hugh: Johannes BRAHMS

(1833-97) Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen (from A German Requiem) (1865-68)

Christ The King: John

TAVERNER (c.1490-1545) Christe Jesu, pastor bone (?)

George Herbert: Ralph

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS (1872-1958) Antiphon (from Five Mystical Songs) (1906-11)

The Choir of Lincoln Cathedral/Aric Prentice, Jeffrey

Makinson (organ), Sgt Tom Ringrose (trumpet)

Rec. Lincoln Cathedral 5-7 June 2018

REGENT REGCD532

With thanks to MusicWeb International where this review was first published.