I will not be the first person to have fallen into the trap of regarding Harriet Cohen as being merely a ‘pendant’ of Sir Arnold Bax. To be fair, I first heard of her through my early ‘study’ of Bax back in the nineteen seventies. The received wisdom suggested that for three decades, she ‘pursued a tempestuous affair with this composer’. When she suddenly discovered that she was not slated to become Lady Bax on the death of his wife, she had an ‘accident’ and cut her wrist whilst carrying a tray of glasses…

Certainly, her colourful

personal life has distracted attention away from her achievements in the ‘recital

room’ or recording studio. Stephen Siek, in the liner notes, suggests that

Harriet ‘as a young woman was beguilingly beautiful, and [that] she rarely

hesitated to advance her career through charm and even seduction.’ He mentions her liaisons ‘real or imagined’

with ‘men ranging from H.G. Wells to Ramsey MacDonald.’ Another issue that causes the biographer

problems is Harriet’s tendency to fabricate –Siek notes that her autobiography

is filled ‘with self-aggrandizing inaccuracies that must be carefully sifted

from the truths that it also contains.’

The ‘gossip’ has partially

obscured a pianist who was not only great but inspired. Her interpretation of

Bach would have been sufficient to have established her reputation for all

time. However, as this present collection of recordings proves, her achievement

extends in many directions.

Out of interest, W.S. Meadmore quotes a story in the Gramophone Magazine

from 1929: ‘When Busoni met Harriet Cohen he looked at her hands and said: "These

are the smallest and worst, hands I have ever seen. It would be impossible to

play the piano with them. You must give music up." Miss Cohen played to

him. He was astonished. He could hardly credit that such hands could make such

fine music.’

A few highlights of

Harriet’s life and achievements may be of interest to those who have not come

across her before. Harriet Pearl Alice

Cohen was born in Brixton, London on 2 December 1895 into a largely musical

household. Her father, Joseph, was an amateur cellist and composer and her

mother, Kathleen Irene, was an accomplished pianist. After piano lessons with her mother, Harriet

attended the Tobias Matthay Pianoforte School. Other pupils at that time

included Myra Hess. In 1908, she gave her first recital – a Chopin Waltz at the

Bechstein Hall! Shortly after this, she won an Ada Lewis Scholarship to the

Royal Academy of Music where she was one of the star pupils. Harriet won ‘a

string of awards’ including the Sterndale Bennett, the Edward Nicholls and the

Hine prizes. She continued her studies

with Felix Swinstead and Matthay himself. Whilst at the Academy she was introduced

to Arnold Bax and became part of the ‘set’ that adored all things Russian in

the wake of Diagalev’s ballet triumphs in London.

One of Harriet Cohen’s

achievements was the ‘discovery’ of the significant vein of keyboard music by Tudor

and other ‘early music’ composers. This included works by Orlando Gibbons,

William Byrd and Henry Purcell. Another important

interest was of Spanish music: she gave the second performance of Manuel da Falla’s

Nights in the Gardens of Spain and

subsequently performed it many times.

However, her major achievement

must be regarded as her exposition of J.S. Bach. The German critic Adolph

Weissmann stated that ‘…so deeply has the spirit of the master entered into her

that she has few, if any, equals as a Bach player’ and no less a person than

Alfred Einstein insisted that ‘she is one of those chosen few who stand among

the elect.’ The Times obituary writer

notes that Harriet played Bach ‘with great musicianship, precision, buoyancy

and an emotional tact which refuses ever to aim at effects outside a true Bach

style.’

Over the years, Harriet

gave the first performances of a number of important works by contemporary

British composers. These included the Piano Concerto by Ralph Vaughan Williams

and Bax’s Symphonic Variations.

William Walton’s Sinfonia Concertante

was introduced by her to France, Spain, Germany and Austria. European composers including Ernst Bloch and

Bela Bartok dedicated works to her. The Soviet composers Kabalevsky and

Shostakovich provided her with new pieces: they are represented on these CDs.

Harriet officially

retired from public life in 1960. Thereafter she devoted much of her time to

the Harriet Cohen International Music Awards and the writing of her

autobiography A Bundle of Time. She

died on 13 November 1967.

It is not my intention to

discuss every number on this superb three CD set – there are 58 tracks each

deserving comment and analysis. However, I will mention a few highlights – at

least from my perspective.

The lion’s share (32

tracks) of this recording is given over to the music of J.S. Bach. There are

three main groupings here. Firstly, there is the important keyboard concerto –

No.1 in D minor (BWV1052). This is presented here in two versions – one dating

from 1924 and the other from 1946. Both are beautifully stated performances; however

the later one is naturally clearer and casts more light on the contrapuntal working

out of the piece. Lewis Foreman has

noted that Harriet was ‘celebrated in her day’ for performances of this work. Once one makes the ‘mental leap’ of hearing

this work on the piano as opposed to the clavier, it can be appreciated as a

most enjoyable execution. I feel that this music is perfectly poised and ultimately

cool in mood.

The ‘pioneering

recordings’ of part of Book 1 of Bach’s The

Well-Tempered Clavier are critical to Harriet’s career. Apparently,

Columbia proposed to issue the entire ‘48’ however, the project never got

beyond the first nine. Her playing of these pieces is pretty near perfect. I

accept that there have been many fine interpreters of these works – my current

favourite is Andreas Schiff. However, Harriet’s commitment to these masterpieces

of the keyboard art is impeccable and combines a superb technical approach to

the music with a ‘lofty intellectual perception’, which is outstanding. It is

only a pity that the set was never completed.

The last element of the

Bach recordings is probably less-popular these days – the transcriptions.

Perhaps the most famous transcriber of Bach’s music is Busoni; however many

other composers turned their hand to this form of arrangement, including Franz

Liszt, Max Reger and Sergei Rachmaninov. Harriet also contributed to this genre

with a number of pieces including the lovely ‘Beloved Jesus, we are here’

(BWV731) and the stately ‘Sanctify us by thy Goodness’ from Cantata No.22.

It may seem a heresy to

many readers when I admit that I am not a huge fan of Mozart’s and Brahms’

piano music. Naturally, I accept that

they are both masters of the keyboard, and concede that it is just the fact

that I have not got to grips with their music.

However, I enjoyed the classical and ‘unsentimental’ rendering of the

Mozart’s C major Sonata K330. The liner notes rightly admit to the somewhat

‘erratic’ tempos of the first movement – one might call it ‘eccentric.’ However,

the slow movement is beautiful and the concluding rondo is perfectly paced.

I am convinced that other

reviewers will extoll the virtues of Harriet’s Chopin and Brahms recordings.

Certainly, I found her interpretation of the Études attractive, if not

revelatory.

The Brahms Ballade in D

minor is a ‘big’ work that was inspired by a grisly Scottish ballad tune,

‘Edward’. Harriet’s performance is

expansive and well-balanced. The closing bars of pianissimo are in perfect

contrast to the macabre earlier pages.

The Intermezzo in B flat minor is a little lighter in mood, but is still

introspective.

I noted above that

Harriet took up Falla’s Nights: alas,

there is no recording of this work available. However, this collection includes

three pieces for solo piano from his pen.

I have always sworn by Alicia de Larrocha for my Spanish piano music;

however, Harriet’s performances of ‘Andaluza’, ‘The Fisherman’s Tale’ and ‘The

Miller’s Dance’ are beholden to no one. The balance between the fire, the

passion and the sultry heat are all ‘present and correct’. These performances

are amongst the highlights of a set of CDs full of highlights!

Stephen Siek notes that

Harriet’s favourite ‘a cappella’ work was William Byrd’s five-voice mass: Elizabethan music certainly appealed to her

as can be heard in the five short pieces from Orlando Gibbons – ‘Ayre’, ‘Alman’,

‘Toy’, ‘Coranto’ and ‘Mr Sanders his Delight’. I have to admit that I prefer

these pieces played on the piano than on the virginal - irrespective of musicological

mores. There is a wistful and melancholic beauty about these timeless pieces

that defies analysis. I do wish that she had recorded more music from this

period. These pieces were taken from Margaret Glyn’s groundbreaking edition of

the composer’s works, first published in 1922. Harriet also included Ralph

Vaughan Williams heart-breaking Hymn Tune

Prelude on [Gibbon’s] Song 13. I feel that this is

one of the most moving pieces that RVW composed.

It is naturally good to

have everything that Harriet recorded from the pen of Arnold Bax. The powerful and demanding Paean (Passacaglia) certainly gives the

lie to those critics who suggested that her small hands limited her technique. She

brings a magic to the ‘Hill Tune’ and to ‘A Mountain Mood’, which is quite

simply perfect. Harriet underscores both works’ largely impressionistic nature.

The

Morning Song (Maytime in Sussex) which was dedicated to Princess Elizabeth

on her 21st birthday is one of Bax’s lighter pieces. Like many of

his late works, it has been considered as lacking in inspiration. However, for

me it is a delight and manages to portray the idealised landscape, which

seemingly inspired it.

One of the pleasures (for

me) of the entire set of discs is the highly charged, romantic and very

overblown – but gorgeous Cornish Rhapsody

from the Gainsborough picture Love Story

starring Margaret Lockwood. This performance was used on the film soundtrack.

The liner notes by

Stephen Siek are excellent and constitute a major essay on Harriet Cohen’s

recording career. It certainly bears careful study both before and after

hearing the music. It would have been nice to have had dates for Messrs.

Gibbons, Bax, and Bath et al: they were given for many of the other composers. There

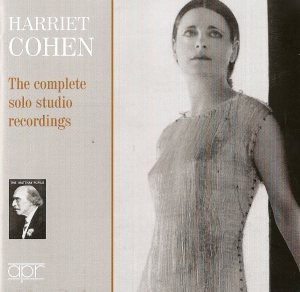

are some excellent photographs of Harriet of both the studio and the ‘snap’ variety.

The CDs themselves are crammed full of music. I guess that they only just

managed to fit in all this music on the three CDs. They are superb values for money -the three

discs are available for around £19.

I have never been a great

enthusiast for ‘historical recordings.’ For one thing, I never know quite what

to expect from the sound quality. Listeners are so used to a pristine reproduction

of sound and look askance at any clicks or hiss. The present three CDs certainly

have some hiss. Could it have been removed? I guess not. However, I was

impressed by the general sound, the pitch seems to be ‘perfect’ and there is

little evidence of where the 78 r.p.m. records would have needed to be ‘turned

over.’

Yet to possess these

three discs I am prepared to forgo my usual reticence to listen to historical recordings.

In fact, I would go as far to say that I would give an arm and a leg to hear

these tracks – complete with a bit of surface noise.

The reader may well divine

that I am still half-in-love with Harriet some 40 years after first discovering

her: that may well be true. However, I would challenge any person to listen to

her performance of Debussy’ Clair de Lune

and not be impressed, challenged and moved.

CD1

J. S. BACH (1685-1750)

Keyboard Concerto No 1 in D minor BWV1052 Orchestra /Sir Henry Wood (1924)

J. S. BACH The

Well-Tempered Clavier Book I: Preludes & Fugues Nos. 1-9 BWV846 - BWV854

(1928)

BACH/RUMMEL Mortify us

by thy grace, from Cantata No 22 (1928)

BACH/COHEN Beloved

Jesus, we are here BWV731 (1928)

CD2

J. S. BACH Keyboard

Concerto No 1 in D minor BWV1052 Philharmonia Orchestra/ Walter Susskind (1946)

J. S. BACH Prelude

& Fugue No 4 BWV849 from WTC Book 1 (1947)

BACH/COHEN Sanctify us

by thy goodness; Beloved Jesus, we are here BWV731; Up! Arouse thee! from

Cantata No.155 (1935)

BACH/PETRI Fantasia

(Praeludium) in C minor BWV921 (1935)

Wolfgang

Amadeus MOZART (1756-1791) Piano Sonata No 10 in C major K330 (1932)

Frederic

CHOPIN (1810-1849) Nocturne Op 15 No 1; Trois Nouvelles Études Nos. 1 & 3

(1943); Étude Op 25 No 7 (1928)

CD3

Johannes

BRAHMS (1833-1897) Ballade in D minor Op 10 No 1; Intermezzo in B flat major

Op 76 No 4 (1930)

Claude

DEBUSSY (1862-1918) Clair de lune, from the Suite bergamasque; La cathédrale

engloutie, No 10 from Préludes Book I (1948)

Manuel DE

FALLA (1876-1846) Andaluza, No 4 from Pièces espagnoles; The Fisherman’s Tale,

from El Amor Brujo; The Miller’s

Dance, from The Three-Cornered Hat

(1943)

Dmitri

KABALEVSKY (1904-1987) Sonatina in C major Op 13 No 1 (1943)

Dmitri

SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) Prelude in E flat minor Op 34 No 14 (1943)

Orlando

GIBBONS (1583-1625) Ayre – Alman – Toy – Coranto – Mr Sanders His Delight

(1947)

GIBBONS/Ralph

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS (1872-1958) Hymn Tune Prelude on Song 13 (1947)

Arnold BAX (1883-1953)

Paean (1938); A Hill Tune (1942); A Mountain Mood –Them & Variations (1942) Arnold BAX Morning Song (Maytime in Sussex) Orchestra/ Dr Malcolm Sargent

(1947) Arnold BAX ‘The Oliver Theme’

from the film Oliver Twist

Philharmonia Orchestra/ Muir Mathieson (1948)

Hubert BATH (1883-1945) ‘Cornish Rhapsody’ from the film Love Story London Symphony Orchestra/

Hubert Bath (1944)

HARRIET COHEN (1895 -1967)

The Complete Solo Studio Recordings

Harriet Cohen (piano)

APR Recordings APR7304

With thanks to MusicWeb International where this review was first published