Edward Gregson is usually

regarded as the doyen of the brass band world. He has composed many successful essays

for this medium. It is less well known that he has written a wide range of orchestral,

chamber, instrumental and choral works as well as scores for film and

television. In recent years this repertoire has begun to be explored on CD. Biographical

information about Gregson is available at his admirable website.

I am beholden to the outstanding

liner notes by Paul Hindmarsh for information and details about all the music

on this new CD. All are premiere recordings.

Manchester Evening News critic Robert Beale, in a review of the first performance of Edward Gregson’s String Quartet No.1 (2014), summed up its impact: “It is an extraordinary work, both gritty and serene. Its three movements are packed with ideas – fugues, variations, cadenzas, a chorale and a march [contained] within the traditional structures of sonata, freely developing fantasia and rondo, and bound together by evolving motives and tonal anchorages providing a sense of journey to a promised land – and he never gives you a dull moment…” I found that despite many stark passages, this quartet is ultimately a progression from darkness to light, or from pessimism to optimism. It deserves a place as one of the most important British quartets of all time.

The Quartet was commissioned by

Paul Hindmarsh as part of the 100th anniversary celebrations of the

Manchester Mid-day Concerts Society. It was premiered by the present ensemble on

14 January 2015.

In 1964, Gregson wrote a Romance for clarinet and piano. This was during his first year at the Royal Academy of Music. The work was revisited in 2016 and was rescored for cor anglais and string quartet. A new title, Le Jardin à Giverny was given, evoking the legendary gardens made so famous by Claude Monet. It is hauntingly beautiful, with long breathed, sinewy melodic lines and nods to the harmonies of John Ireland. It would not surprise me if this were taken up by Classic fm. The revision was dedicated to the present soloist, Alison Teale.

The fact that Triptych for solo violin (1988) was originally a test piece devised for the Royal Northern College Music’s Manchester International Violin Competition should not put the listener off. This is not a dry as dust, pedantic score designed simply to stump the soloist. Gregson has written that, “Although the main requirement is to produce an exacting technical test, a composer must try and avoid the ephemeral nature of such a task and create something more universal.” I believe that he has successfully met this challenge. As the title implies, the work is presented in three hugely contrasting movements. The opening, A Dionysian Dialogue is a musical realisation of the basic human dichotomy – “the Dionysian music is raw, earthy, sometimes violent, often ecstatic; whereas the Apollonian is serene, dream-like, calm, assured.” This movement is full of allusions to Bach and Walton, Shostakovich and Stravinsky, reflecting Apollo and Dionysius respectively. The second movement is a “song without words.” The structure is that of a theme with two variations, with a “nostalgic” return of the theme with a fadeout. Technical wizardry abounds, especially in the second variation’s double stopping. The finale, a Moto perpetuo is a fusion of Italian and Hibernian mores. Based on the tarantella, it somehow morphs “into an Irish jig, where previous chromatic elements are transformed into diatonic ones.” And the foot-tapping sounds are not faults on the disk. It is encouraged by Gregson. The Triptych was revised in 2020 for the present recording.

The Benedictus for alto saxophone and string quartet is another adaptation. Originally part of Missa Brevis Pacem (a short mass for peace composed in 1988, for boys’ voices, baritone solo, large symphonic wind ensemble and a battery of percussion). In 2021, the Benedictus section was recreated as a chamber music work. The original boy treble solo is taken up by the saxophone. It is a moving exposition of a simple melody supported by reflective string writing.

The String Quartet No.2 (2017) is remarkably satisfying. Although conceived as a single movement, it conveniently subdivides into five clear sections. The opening Siciliana is retrospective in impact: it generates much of the material for the succeeding divisions. A faster Alla marcia section follows which presents harmonically and contrapuntally dissonant material of considerable interest. The central section, Come prima (Appassionata) builds on the opening Siciliana, and leads to a “powerful and passionate climax.” A “fleet of foot” Scherzo follows before the confident return of the quartet’s opening material. Edward Gregson has stated that this is “a simple melodic utterance in modal G major – eventually subsiding into a codetta with upward glissandi harmonics, before fading into the silence from whence the music first began its journey.”

I cannot fault anything about this CD. The performance by all concerned is extraordinary. The quality of the recording is superb. The liner notes, as noted above, by Paul Hindmarsh are clear, helpful and informative.

All five premiere recordings

reveal great depth, vision and technical assurance. I look forward to further

explorations Edward Gregson’s music on the Naxos label.

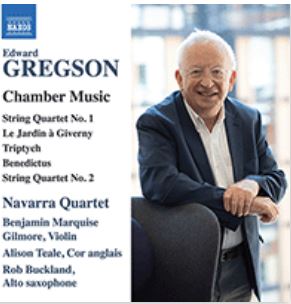

Edward GREGSON (b.1945)

String Quartet No.1 (2014)

Le Jardin à Giverny for cor anglais and string quartet (1964/2016)

Triptych for solo violin (2011, rev. 2020)

Benedictus (1988) (version for alto saxophone and string quartet (1988/2021)

String Quartet No.2 (2017)

Alison Teale (cor anglais), Rob Buckland (alto saxophone)

Navarra String Quartet

rec. 20-21 November 2021, St John the Evangelist, Upper Norwood, London

NAXOS 8.574223

With thanks to MusicWeb International where this review was first published.