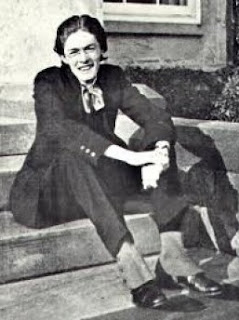

Arthur Eaglefield Hull (1876-1928)

was a British music critic, author, organist and composer. He wrote for many

periodicals, including The Monthly Musical Record. His books include an

early biography of Cyril Scott (1919) and Modern harmony, its explanation and

application (1915). He edited the organ works of Alexander Guilmant. His life

ended in tragedy when he fell in front of a train at Huddersfield Railway

station. The coroner reported “Suicide whilst of unsound mind.”

I have provided a few footnotes

and have made a few orthographical changes to the text.

FIFTEEN YEARS AGO, THE WORK OF WILLIAM BAINES would have been impossible in England. Fortunately for him, as for many others, the whole artistic outlook has now changed, not only in Britain, but all over Europe. In 1914 the great Russian composer, Scriabin, replied to an article by Briantchaninoff in the Novoe Vremia [1] on the educational significance of the war, saying “You have voiced and old idea of mine, that at times the human mass needs to be shaken up in order to purify itself and to fit it for the reception of more delicate impressions (vibrations) than those to which it has hitherto responded.” The upheaval of the war was not however the only cause of the improved outlook; but it was the chief contributory one.

In the realm of British music tocsins [bells] were rung by Parry with his Prometheus Unbound in 1880, Stanford with his Irish Symphony in 1887, and by Mackenzie with his Britania Overture in 1894; but the nation at large was unable to respond – perhaps because the ringers themselves could not be quite wholehearted on their summoning, for they were all three trained on German lines. And the land rested for another term of years until Elgar came with his Gerontius in 1900, speaking at last in the pure English musical tongue, and Bantock followed with his Omar Khayyam, flinging the door wide open to the East, and Holbrooke with his Ulalume, rating an indolent public for its bovine deafness. Then the war shut off our musical intercourse with Germany for seven lean years, during which times we discovered the new musical schools of Belgium, France, Spain, Italy and Finland, the significance of India and Japan in art, and incidentally our own national musical soul, with its shallow musical hypocrisies, its immense inheritances, and its glorious possibilities. We discovered Bax, Ireland, Bridge, Butterworth, Goossens, Holst, Vaughan Williams and many others. And during their naissance, a small boy reared in circumstances so humble that they allowed no musical training, only sparse opportunities of hearing good music, hardly any books ever, was weaving music of an unusual beauty and a rare originality, out of nothing.

One day in January 1920, I arrived home late at night tired out by a long journey. Turning listlessly over a stack of new music on the piano, the title Paradise Gardens caught my fancy, and the first few bars arrested my attention. Here was an unknown composer writing in all the splendour of Scriabin’s piano style, but with an individuality swung in an altogether different direction. I played through Paradise Gardens with keen interest and repeated it with wonder and admiration. A rare melodic gift, an originality of expression, a dainty but logical harmonic invention, an attractive personality, and a Japanese exquisiteness of perfection, all floated out from the tones of my Blüthner grand. The piece was a well-sustained reverie, full of delicious motives and fragrant tone-colours. I turned to the only other copy of Baines in the stack of new music, a set of Preludes, wondering who the new composer could be. These proved to be seven delightful miniatures in varying moods. The first had some Scriabinic turns of harmony yet possessed individuality. The second written in a convent garden, [2] contrasts the delicate sounds of a blackbird’s notes with the turmoil of the composer’s ow feelings, concluding with a waft of organ sound. The third is an eight-bar harmonic miniature, a gem of the rare order of the Chopin C minor prelude. In the fourth I found a whirl of gyrating patterns of harmonic play, like a sun dust dance; the fifth a sketch of poppies gleaming in the moonlight; the sixth, an exquisite piece like nothing else in the world; the final piece, I thought, spoilt a lovely set. The first six pieces all moved with a delightful life. The style was thoroughly steeped in the essential colour of the piano but was free of the Chopin morbidezza. [3] Only Debussy and Scriabin has written for the piano. I placed the pieces aside to show to my friend William Murdoch who was visiting me on the following night.

He read them off at sight in a

wonderful way, was impressed, and promised to put them into his programmes.

Meanwhile I wrote to the publishers and found that the composer was a youth of

nineteen, living in a small Yorkshire town, Horbury and was on the point of

moving to York where his father was fulfilling an engagement as a cinema-pianist.

Baines came and stayed with me, bringing shoals of unpublished manuscripts,

quartets, songs, a symphony - more piano pieces. I was confirmed in my hope and

was pleased meanwhile to read an unusually appreciative notice of two Baines

pieces, by Mr Dunton Green in the Arts Gazette. I could not conceive how

the other critics had overlooked such striking music; so, I determined to sound

a loud fanfare, and opened an article on the new pieces in the British Music

Bulletin (March 1920), [4] which I then edited, with the ecstatic cry of

Schumann over Chopin’s early pieces, “Hats off, gentlemen, a genius!” Since

then, the composer has become widely known in the North, giving recitals of his

own music to a large and ever-growing following at such places as his health

permits him to visit – Manchester, Sheffield, Liverpool, Leeds, Huddersfield,

etc. Mr Frederick Dawson, [5] the famous pianist, has recently become an

enthusiastic propogandist of Baines’s music and a warm friend to the composer,

whose future seems now to be assured, provided sound health can be won.

[1] A.N. Brianchaninov (1874-1918?) was a Russian music critic and editor of the magazine New Link. He was a friend of Alexnader Scriabin and was an enthusiastic proponent of his music.

[2] This is most likely Bar Convent in York.

[3] Morbiezza: an extreme delicacy and softness

[4] The British Music Bulletin was the house journal of the British Music Society founded by A. Eaglefield Hull in 1918 “with the intention of advancing the cause of music in Britain on every conceivable front.” It is no relation of the present British Music Society which was founded in 1979.

[5] Frederick Dawson (1868-1940) was a Leeds born pianist and teacher. He taught at the Royal Manchester College of Music and at the Royal College of Music in London. Dawson had a wide-ranging repertoire from the early English music to the French Impressionists.

To be continued…

No comments:

Post a Comment